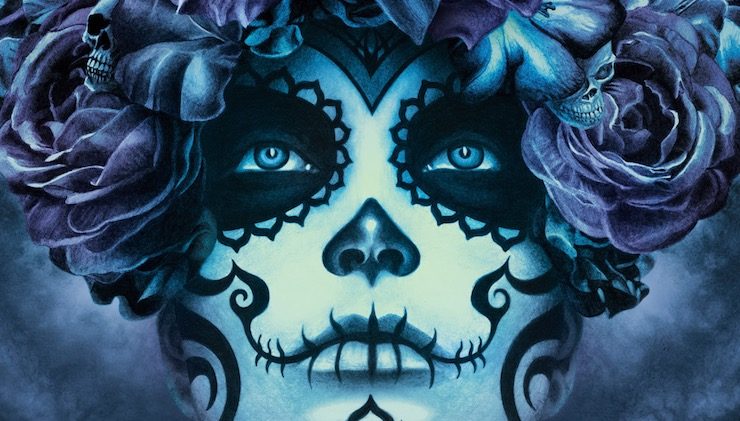

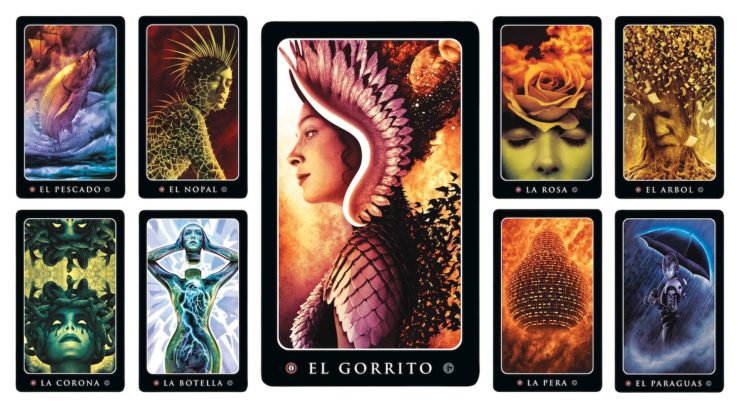

I’ve been illustrating covers for major science fiction, fantasy, and horror publishers for two decades, but after I won my first Hugo Award in 2012, I decided to start creating my own worlds and stories. In between cover jobs, something was building—I was inspired by the icons of the classic Mexican game of chance, Loteria, that I grew up playing with my family. So I started drawing. I’ve been producing very limited runs of the artworks as giant-sized art cards called “Loteria Grandes”—and it’s a joy to watch that fan base grow. What I didn’t know is that the pictures contained secrets and stories, and the more that I drew, the more they revealed themselves.

So I started writing them down.

It’s been a learning process, but now as these words and pictures coalesce into a formal book proposal, I’ve been carefully observing several of my fellow pros—Brom, Ruth Sanderson, Charles Vess, Jeffrey Alan Love, Todd Lockwood and more—as they blaze their own contemporary trails in graphic storytelling, as writer AND illustrator. For decades, we’ve experienced illustrated children’s’ picture books created by singular voices, but we’re seeing more and more artists successfully writing and illustrating their own novels and graphic stories for adults as well. Debuts only happen once, so I want to ask two new artist / authors to share how they created their freshly-painted universes. Meanwhile, another visionary artist has been astounding audiences for years with magical tales of lost things, strange suburbias, and rules of summer, and I want to hear how he makes images and texts dance.

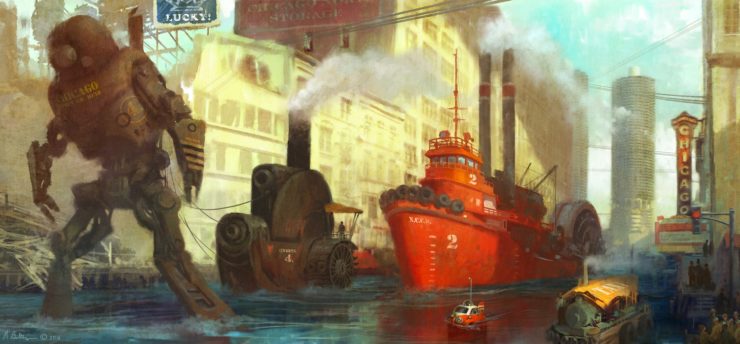

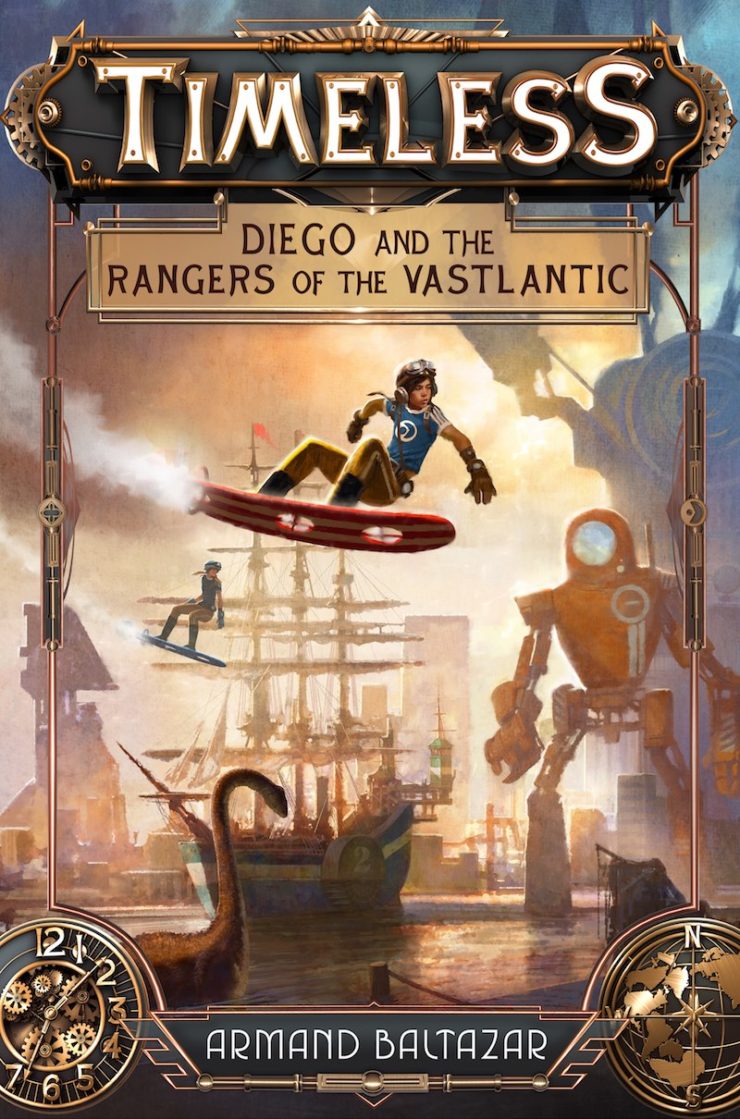

Hamilton King Award winner Gregory Manchess’ Above The Timberline is a lavishly painted novel about the son of a famed polar explorer searching for his stranded father, and a lost city buried under snow. Armand Baltazar’s Timeless presents four extraordinary children who must save the day, amidst a world where dinosaurs, pirates, and giant robots roam the earth. Shaun Tan’s latest masterpiece is The Singing Bones, a singular reshaping of the Brothers Grimm’s tales in words and sculptures that are as primal as they are unsettling.

I hope you all will enjoy eavesdropping. Onward!

(Click any image to enlarge.)

All of us have spent large parts of our careers creating illustrations to complement a set of words, but when we’re creating our own graphic narratives, those rules don’t necessarily apply. For example, pictures can initiate the words. How did the relationship between your words and your pictures evolve as you created your narrative?

GREGORY MANCHESS: My story started with one painting. I worked on-camera to create it for a video about my painting process. People responded so positively to the image that I thought I might be able to write a visual novel using the image as a hook.

The words came from the first painting, but as I progressed with the story, I sketched more images and these lead to more ideas. Those led to more images. I wrote back and forth—sketch to story; story to sketch—until I had a full-size novel. Then I went through it all again and searched for how I could cut exposition down to a tight combination of words and pictures, telling the story visually for what didn’t need words, and writing for what I couldn’t show.

I steered away from comic panels as that was like being too word-driven. It would’ve complicated the broad pages and showed too much information. I designed each spread to depict moments, to tell much of the story visually, combined with the words—not simply repeating the words.

ARMAND BALTAZAR: I spent a good part of my career as a visual development artist for animated films. Visual development to me differs slightly from concept design for film in that as a concept designer, the emphasis for the concept artist is on creating design solutions and possibilities in service of the story and scenes as they are written in the script or treatment.

In contrast, a lot of visual development I’ve worked on in animation have had very little if no script to begin with. Often we’d be given character ideas (in words) with general ideas of where the story may go and with what the arc of the story might be and who the characters are at that stage of development.

In animation, a character can go from being a person to a squirrel to becoming a talking toaster in the end. Visual development for animation also differs in that we are using the art to explore and build possible story points and define character’s arcs through situations and scenes. Vis-dev artists work closely with storyboard artists and in a sense we are writing out the visual first draft of the story with pictures.

I used a variation of this process in writing and creating the art for my book. I started by creating the characters and making them as real as possible through my sketches, drawings, paintings and maquettes. Then I would write about them in my notebook giving them histories, personalities, and motivations. Afterwards I would write or sketch the situations they were in to visualize and propel the narrative. All of that helped me to outline the story and visual structure of the book.

Armed with an outline and a handful of paintings, I was able to get back to the computer to write the rough draft of the story. As time passed, I refined my process and would alternate between writing and drawing to build the story, occasionally stopping along the way to craft paintings to test the strength and clarity of the illustrations against the words I wrote. It was a very organic process.

SHAUN TAN: The best analogy for me is ping pong. Either form can serve up an initial impression, as words or pictures, and then the volley begins. The image might suggest a narrative, in part through the accidental tangents of line, especially when I work quickly and loosely with a biro in a small sketchbook which encourages mutation as much as definition. They will spawn other impressions.

I will then think about narrative for a while, and a written vignette might evolve which has its own pressures, character and ambition. Like sketchy lines, words have lives of their own, or a voice that seeks a certain resolution. So then it’s back to pictures to respond to that. The final result can be either close to the initial impression, only more simple and refined, or else completely different, depending on how this evolution goes.

This ability to play words and images off each other is not just a way to create a visual narrative—it’s a way to think. Even if I end up dispensing with either words or pictures in the final work—a piece of text or a painting—the duality of this approach is useful for getting to a certain point, to sort out good and bad ideas.

What was the balance between the making of your latest book and the rest of your life, professional and personal? What other work did you do while you were creating these books, and how did you strike that balance? What did you do to pay the bills while creating such an immersive narrative project?

GM: I’d been planning the book for five years, hoping I’d be able to sell it to a publisher at some point soon. Over that time, I saved as much money as I possibly could, knowing that most publishers would not be able to pay for what it would take to do 100+ paintings.

So once the book was sold, I combined my savings with the book advance and lived frugally over the following year while I painted. I didn’t take on any work except for what I had already promised to finish. I also used credit cards, to keep the cash flow strong. I’m still paying those off. Might be awhile before I clear that up!

AB: My personal life was a difficult thing to manage. You get in a rhythm waking up and driving to a studio job five days a week. My wife and son had a schedule and routine that synced well with mine. Becoming an author-artist, husband, and dad who lived and worked at home 24/7… changed all of that. We went through a lot of growing pains that first year reconfiguring “life 2.0” as our new operating system. We eventually worked it out and in the end I can honestly say that the experience has only made us stronger and better as a family.

After I finished work on Pixar’s Inside Out, I left the studio to focus and work on Timeless full time. I’d saved a decent amount of money to live but took on a lot of freelance work in the beginning just to be safe. I did a lot of character design, set design, and visual development work for animated projects. Later on I was able to stop freelancing when my Timeless book & series was picked up by HarperCollins Publishing and then serendipitously optioned by Twentieth Century Fox to be developed as a feature film. The combination of the publisher’s advance and studio option paid the bills and allowed me to complete the book.

ST: Yeah. It’s not just about money. It’s about time, especially when you have a family. I’m in quite a fortunate position in that I have generated enough picture books over the years that the small royalties from each add up to a semi-dependable basic wage, and I will occasionally sell work through exhibitions to make up the rest, as well as limited edition prints.

Prior to that, I tended to divide my time between personal projects and commercial projects. The personal ones were weird paintings and books that nobody was particularly asking for (the best kind) and the commercial work tended to be book covers, educational books for reluctant readers, painting commissions, workshops with kids and the many other things that illustrators do to make ends meet, which are usually prescribed by a client. As the personal and weird books grew in popularity, I was able to gradually shift more time into that side of things—which is interesting, because I originally started doing those projects as a way to keep busy when the commercial work was a bit thin.

I kept thinking ‘these will never make money like the commercial work, but they feel far more creative and satisfying at least’, and then in the long term, they’ve actually been a far more profitable commercially too. All the way along, however, I was careful to assess the balance. You can’t have safe space to think freely if you aren’t already paying the rent!

The shelf space in a Barnes & Noble has shifted a lot in recent years. I think in the last year or so, we’ve seen less and less floor space dedicated to books and more of it dedicated to games, toys, stationary, vinyl and non-literary products. I suspect some book publishers may see increasing advantage to publishing projects that can use the rest of that non-book space to attract audiences toward their books—”owning” multiple spots of product space within a store. How can visual artists take advantage of that opportunity and light the way for publishers? Do you have interest in exploring that non-book space through your work—or do you have sights positioned elsewhere?

GM: As artists we have the rare ability, and now opportunity, to use visuals to push our ideas to an audience and communicate story within moments. Authors desperately need a time commitment from readers to get their ideas across. I can create an image for my story to hold a potential reader’s curiosity and get them to stay in the moment, building a compelling desire to find out more. This is extremely practical for gaining attention to a work. It’s the work that book jackets do for a novel.

Images are powerful in the way they command attention. Authors are always working hard to get that strength into their stories. As an artist I’ve learned how to do this through composition, value, and light—all the visual basics our brains use everyday to decipher the world around us. It works because it stimulates a broader area of the mind all at once, and this is exciting.

I want to use those other non-book areas in bookstores to gain attention for my work. Related products such as toys or games, posters or prints, pull an audience toward your idea faster than waiting for a reader to stumble over a book cover and hope they’ll be interested. Eventually, I believe book marketers will see how other merchandise can gain attention for a story, and use it to drive a narrative, and thereby, sales. This will push reviewers toward a work as well.

All publishers know the most effective way to advertise any story is word-of-mouth. But how do you create that before the time it takes to read a work? Images.

AB: The evolution of bookstores, whether they be corporate, independent, or comic has been a fascinating and occasionally heartbreaking thing to see over the years. The industry has had tectonic shifts in technology and culture that have reshaped and at times nearly wiped out their existence. But like all things that have endured, the bookstores have adapted to change.

The integration of pop culture and related media merchandise along with services like boutique coffee has been a necessary evil for most diehard stores. Personally I think it’s a fantastic opportunity for artist/storytellers to capitalize on. We can bring art, collectibles, games and other merchandise based on our books into the stores.. And…ok I’ll say the word…synergy. I think that if you can create a wonderful story and art in your books, you can also help the store and your book sales by incorporating these things.

As for me, Timeless is part of both HarperCollins and Twentieth Century Fox, so all the things I might do with my book series will be in partnership with them. I would love to see some high quality collectible figurines, art prints, and related books in stores in the future.

ST: It’s a bit different here in Australia. We don’t have Barnes & Noble, but as a US-published author, I’m most certainly part of that shift. I have explored things beyond books a little, but not a great deal. I enjoy sculpture for instance, as in the work I produced for The Singing Bones, but even then it was to photograph them for a conventional book!

To be honest, I don’t think so much about the market or those other opportunities, so long as books are doing okay. For some years, I’ve been producing my own limited edition prints, basically to meet demand from readers (and also to control image quality, which is never ideal in a printed book). I’m open to toys and things like that for the same reason—although my occasional forays into these areas have been time-consuming and dominated by production and distribution logistics. Not terribly appealing. I’ve also worked on apps, films, theatrical adaptations and so on, but at the end of the day—my overriding interest is books, and particularly picture books. So I will keep working in this relatively simple medium for as long as it can be sustained.

What perspectives can you offer to prose authors as a visual storyteller that might expand the possibilities for their own working processes and storytelling?

GM: I’d suggest learning to draw, but it takes as much effort to learn good drawing as good writing. It can be done though. I encourage my students to do this anyway. If they start early to draw and write, both endeavors will bolster each other.

Prose authors can gain a great visual conscience by taking graphic design and drawing classes, to learn the basics of how an image goes together. After all, the depth created in a picture is nearly the same as building depth in character, landscape, scene-building, not to mention what it takes to ‘build a world.’ Learning what creates a good moment in a painting will allow them to design better images with words.

Many prose stories have no graphic sense for designed costumes, landscapes, characters. It reads as visual mishmash if color and light aren’t considered. Even designing the movement within a scene can be built using graphic design. How a character moves through a scene, how they stand, how they deliver speech—all body language is built from the same principles.

Some of the most popular stories have been based on a powerful graphic vision: Dune, Narnia, Harry Potter, A Princess of Mars, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Hunger Games, etc.

AB: When I’ve talked about the craft of writing and illustrating stories with author friends, we discovered a great deal about the visual storytellers’ approach is useful to them. Visual storytellers often think of storytelling in terms of composition, design, lighting, color, and execution. The story manifests as a series of images that are performed, shot, edited, and even scored in our minds—at least that’s what happens in my head! Writers who strive to elevate the imagery in their writing might find it helpful to sketch out their ideas and study what is working, or they can collect and study photographs that resonate with the emotion and mood of what they are going for. The images they draw or collect may even open up narrative possibilities. I think a lot of good writers look for the poetry in words, and I found that using visuals (even if only as reference for a prose author) can help their words to create poetry in the mind’s eye.

One of the things that can strengthen a visual storyteller’s writing skills is a technique we have in common with writers. Writers craft words to reveal what is absolutely necessary to the story first, incorporating only the details that help with what the story needs and removing what doesn’t. Good writers are rich in world building and description and use those details where they need to be, but must be willing to as they say “kill your darlings” or remove that which takes away from the strength of the story. These principles are fundamentally in line with what makes great narrative illustration, look at any N.C. Wyeth and Frank Frazetta painting, or even a scene in any number of Walt Disney’s classic animated films and you will see these principles at work. Like making a great painting, what you leave out or have to throw into the shadows or out of focus is just as important as what you’ve put in. I was amazed and delighted to approach writing prose in that way…it made total sense as an artist.

ST: I would agree that if you have any facility for drawing—and drawing is primarily about articulating conceptual ideas, it doesn’t have to progress beyond stick figures at all—I would try augmenting text with doodles. And yes, I also surround myself with visual references or mood boards, mostly things gleaned from the internet (in my early days I a lot of my time was spent trawling through libraries, looking for useful visual references) and these must surely be useful to a prose author also—if only to knock your train of thought off the rails a bit when you pause to look up from your writing desk. The instant randomness of images can be a potent stimulus, and the unexpected collision of unrelated things is often a source of inspiration.

What did you learn from your latest author experience that you wish you’d known when you started? What are the lessons you’ll take into the next one—whether from the creative end or the business / publicity side?

GM: LOL! Good question, John! As my book gets closer to release, I’m still learning!

Honestly, I wish I had trusted my desire to write and just get down to it sooner. A good friend told me, “All good writing is re-writing.” I wasn’t sure what she meant at the time. Then I read a post about the Zero Draft, and I understood immediately.

I had thought that the first draft should reflect the final wording and plot of a book. Considering a Zero Draft lets a writer pour words onto a page, tamp down their inner-governor, and allow their natural instincts for the story to come out, sometimes without realizing what they had inside. The Zero Draft gets rid of that voice that questions one’s every move.

Like a simple sketch, where the artist is looking for the right shapes and values, the earliest prose draft is similar. Once much of that initial drive for the story is out on the page, an author can go back to review, augment, and rearrange the story to build a stronger narrative, as an artist cleans up a drawing, or refines a painting.

One visual lesson I’ll take from Above the Timberline is to get images onto the page faster. No hesitation. Let the drawings reflect the story back to my critical mind that’s trying to cover up mistakes or embarrassments. Let the fuzzy vision of “not sure” become reality when the drawing demands clarity. An artist thinks on paper.

AB: I learned that it is very important to know who you are writing for. Much like working on an illustration or concept design; knowing what kind of story you are creating, what kind of medium…book cover, comic book pencil layouts for panels, a set design for an establishing shot that needs to be mindful of the camera move and the duration of the shot…etc. Having a complete grasp on these parameters and limitations enables you to create successful visual design, illustration, and storytelling. Likewise in writing. When I first wrote my story I wish I’d thought more about the length, audience, and specifically the age of the audience I was writing for. I learned that these things have a direct relationship with both the people who’ll want to buy your books, and the business of actually producing the book. It made me double back, edit, and rewrite to make a better story that would work well for the audience it was intended for. It is prudent to have an understanding of how the book industry works, and if you don’t know…find out!

Other words of advice I’d share is…write, write, write in your notebooks with the same passion and dedication that you…draw, draw, and then draw some more in your sketchbooks! Never stop writing or drawing! Step 1: Constantly learn. Step 2: stay humble. Step 3: work harder. If you stumble dust yourself off and repeat steps 1 through 3. Get yourself a good agent, one that gets what you do and wants to help you connect with the right publisher, this makes a huge difference. The same can be said for the potential publisher. Don’t be put off by rejection…it’s a lot like submitting your portfolio for work. Not everyone is going to be right for what you have to offer, and you won’t be right for what everyone wants to publish as well. Concentrate your efforts towards publishers that release the kind of books and stories that are in line with what you love and do. Understand that every rejection is bringing you closer to the right publisher!

ST: My main advice is—plan well, and just start cranking out images. Test the ideas patiently. I tend to spend too much time at the conceptual stage perhaps, drawing lots of thumbnail doodles, but not developing them further. Then I’ll get interrupted by another project, return later to the thumbnails, and find them a bit clunky and uninspiring, and redo them. This can happen again and again, almost endlessly.

However, if I spend a bit of time working up some thumbnails into concept art, as more developed drawings with atmosphere and detail, it’s a lot like putting kindling in a fire. I get a little bit of inspiration from a good drawing, a bit of feedback, which might prompt me to invest in another one, and so on. It’s important to fan that little flame to a point where the enthusiasm becomes self sustaining. If I just keep thinking about a project, without doing any demonstrative artwork, it’s a constantly firing spark that is likely to die out.

A good idea by itself is nothing. There must be action. There must be work. Sometimes, when a book project seems daunting, or at risk of devolving into confusion (which is often!) I will take just one page to completion, and have that on my wall as further inspiration, as well as to say ‘yes, I can do this.’ The imagination needs constant encouragement. It doesn’t just power on all by itself.

Gregory Manchess has worked as a freelance illustrator for nearly forty years on advertising campaigns, magazines, and book covers. His work has appeared on covers and for feature stories of National Geographic, Time, The Atlantic, and Smithsonian. Gregory’s excellent figure work has led to numerous commissions for stamps by the US Postal Service, including the Mark Twain stamp and the recently released March on Washington stamp. Widely awarded within the industry, Manchess exhibits frequently at the Society of Illustrators in New York. His peers at the Society presented him with their highest honor, the coveted Hamilton King Award. Gregory is included in Walt Reed’s latest edition of The Illustrator in America, 1860–2000. He lectures frequently at universities and colleges nationwide and gives workshops in painting at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, and the Illustration Master Class in Amherst, Massachusetts. Above the Timberline publishes October 24th with Saga Press.

Armand Baltazar was born on Chicago’s North Side, not far from the famed Wrigley Field. After attending the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Armand began a visual storytelling career in feature animation as a background artist, visual development artist, and art director for DreamWorks Studios, Walt Disney, and Pixar Animation. He currently resides in Northern California with his family, creating the art and stories for the epic adventure series Timeless, available from HarperCollins.

Shaun Tan is the New York Times-bestselling author and illustrator of the award-winning graphic novel The Arrival as well as Tales from Outer Suburbia; Lost & Found: Three by Shaun Tan; The Bird King: An Artist’s Notebook; and Rules of Summer. His latest release is The Singing Bones, a collection of tales told in sculpture and text, for which Shaun says, “It’s like when you wake up from a bad dream—you never remember the whole dream, you remember the most disturbing part. So I eroded these stories down.” He won an Oscar for his short film The Lost Thing based on a story in the book Lost & Found. He is also the recipient of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award of his contribution to children’s literature. Shaun lives in Melbourne, Australia.

John Picacio is one of the most acclaimed American artists in science fiction and fantasy over the last decade, creating best-selling art for George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, as well as the Star Trek and X-Men franchises. His body of work features major cover illustrations for authors such as Michael Moorcock, Harlan Ellison, Brenda Cooper, James Dashner, Dan Simmons, Mark Chadbourn, Sheri S. Tepper, James Tiptree, Jr., Lauren Beukes, Jeffrey Ford, and Joe R. Lansdale. Winner of the 2012 and 2013 Hugo Award for Best Professional Artist, his accolades include eight Chesley Awards, two Locus Awards, two International Horror Guild Awards, the World Fantasy Award, and the Inkpot Award. He is currently writing and illustrating a Loteria book. His literary works are represented by Joanna Volpe of New Leaf Literary and Media (NYC).